Conservation

Orangutan Range

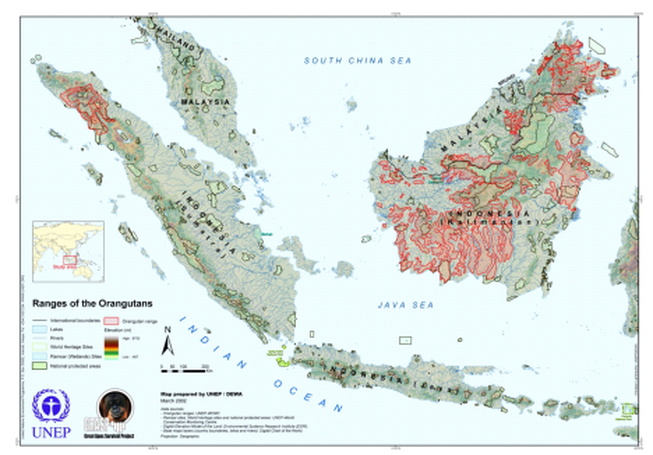

Orangutans are the only great apes occurring outside Africa, and live in dramatically declining forest habitats on the islands of Borneo and Sumatra.

Orangutans are the only great apes occurring outside Africa, and live in dramatically declining forest habitats on the islands of Borneo and Sumatra.

Status

The Bornean orangutan occurs in forests in two of the three nations sharing the island: Indonesia (Kalimantan) and Malaysia (Sabah, Sarawak). The Sumatran orangutan occurs only in the provinces of Aceh and Sumatera Utara in northern Sumatra, Indonesia. The Tapanuli orangutan are only found in the Batang Toru Ecosystem, in the three Tapanuli Districts of North Sumatrai.

Estimates of the numbers left in the wild vary. Most recent estimates indicate that fewer than 14,500 (Serge Wich) Sumatran orangutans remain in the wild today. In Borneo, given the greater understanding of the extent of the orangutan's range, the original 2004 estimate of ca. 54,000 individuals was revised in 2016 to 104,700 individuals (https://www.iucnredlist.org/details/17975/0). However, this estimate does not accommodate population declines during the period 2004-2016. A revised population estimate is anticipated in 2017, and is expected to incorporate a projected Bornean orangutan population decline of more than 55% by 2025 (Wich, 2017, pers. comm.). Based on this information, the Orangutan SSP estimates that the populations of Bornean orangutans in the wild number at least 78,500 (Voigt et al, 2018 and Santika et al, 2017)

There is debate as to the rate of population decline, with estimates suggesting a loss of between 3,000 and 5,000 individuals every year. While the rate of decline may be debated, the trend may not: the survival of the orangutan is becoming more precarious with every passing year, with extinction in the wild likely to occur within 10-20 years in the absence of effective protection of habitat.

The Bornean, Sumatran and Tapanuli species are now ALL classed as Critically Endangered by the World Conservation Union (IUCN), and are listed on Appendix I of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES). The U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service lists both Bornean and Sumatran species as Endangered on its Endangered Species List.

The newly discovered critically endangered Tapanuli orangutan has now appeared on the IUCN's list of the 25 Most Endangered Primate species in its 2018-2020 update.

Except for the 2010 and 2012 editions, the Sumatran orangutan species had been included in every "Top 25" listing since the list's inception in 2000 until this most recent edition. “The purpose of our Top 25 list is to highlight those primates most at risk, to attract the attention of the public, to stimulate national governments to do more, and especially to find the resources to implement desperately needed conservation measures,” says Dr Russell Mittermeier, Chair of the IUCN/SSC Primate Specialist Group and Executive Vice Chair of Conservation International.

The Bornean orangutan occurs in forests in two of the three nations sharing the island: Indonesia (Kalimantan) and Malaysia (Sabah, Sarawak). The Sumatran orangutan occurs only in the provinces of Aceh and Sumatera Utara in northern Sumatra, Indonesia. The Tapanuli orangutan are only found in the Batang Toru Ecosystem, in the three Tapanuli Districts of North Sumatrai.

Estimates of the numbers left in the wild vary. Most recent estimates indicate that fewer than 14,500 (Serge Wich) Sumatran orangutans remain in the wild today. In Borneo, given the greater understanding of the extent of the orangutan's range, the original 2004 estimate of ca. 54,000 individuals was revised in 2016 to 104,700 individuals (https://www.iucnredlist.org/details/17975/0). However, this estimate does not accommodate population declines during the period 2004-2016. A revised population estimate is anticipated in 2017, and is expected to incorporate a projected Bornean orangutan population decline of more than 55% by 2025 (Wich, 2017, pers. comm.). Based on this information, the Orangutan SSP estimates that the populations of Bornean orangutans in the wild number at least 78,500 (Voigt et al, 2018 and Santika et al, 2017)

There is debate as to the rate of population decline, with estimates suggesting a loss of between 3,000 and 5,000 individuals every year. While the rate of decline may be debated, the trend may not: the survival of the orangutan is becoming more precarious with every passing year, with extinction in the wild likely to occur within 10-20 years in the absence of effective protection of habitat.

The Bornean, Sumatran and Tapanuli species are now ALL classed as Critically Endangered by the World Conservation Union (IUCN), and are listed on Appendix I of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES). The U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service lists both Bornean and Sumatran species as Endangered on its Endangered Species List.

The newly discovered critically endangered Tapanuli orangutan has now appeared on the IUCN's list of the 25 Most Endangered Primate species in its 2018-2020 update.

Except for the 2010 and 2012 editions, the Sumatran orangutan species had been included in every "Top 25" listing since the list's inception in 2000 until this most recent edition. “The purpose of our Top 25 list is to highlight those primates most at risk, to attract the attention of the public, to stimulate national governments to do more, and especially to find the resources to implement desperately needed conservation measures,” says Dr Russell Mittermeier, Chair of the IUCN/SSC Primate Specialist Group and Executive Vice Chair of Conservation International.

Photo from Sydney Morning Herald, April 2012

Photo from Sydney Morning Herald, April 2012

Threats

The species’ survival is severely endangered by logging, forest fires including those associated with the rapid spread of oil palm plantations, illegal hunting and trade. In the last few years, timber companies have increasingly entered the last strongholds of orangutans in Indonesia: the national parks. Official Indonesian data reveal that illegal logging has recently taken place in 37 of 41 surveyed national parks in Indonesia, some also seriously affected by mining and oil palm plantation development. Satellite imagery from 2006 documents beyond any doubt that protected areas important for orangutans are being deforested. The use of bribery or armed force by logging companies is commonly reported, and park rangers have insufficient numbers, arms, equipment and training to cope.

If current logging trends continue, most of Indonesia’s national parks are likely to be severely damaged within the next decade, because they are among the last areas to hold valuable timber in commercially viable amounts. The rapid rate of removal of food trees, killing of orangutans displaced by logging and plantation development, and fragmentation of remaining intact forest constitutes a conservation emergency. More than 1,000 orangutans are living in rescue centers in Borneo alone, with uncertain chances of ever returning to the wild.

Orangutans are unable to survive long-term in degraded and fragmented forests. Their fruit-dominated diet requires them to occupy large ranges to ensure sufficient supplies, and some individuals commute between feedings sources. Devastated forests offer few fruit resources and orangutans are forced out to roam in search of food. Large numbers were massacred while fleeing the flames and smoke during and after the extensive forest fires of 1997 and 1998. Similarly, orangutans do not cope well with selective logging. Selectively logged forest and old secondary growth contain only 30%-50% of the orangutan density found in primary forest.

To add pressure to the situation, orangutans have a comparatively slow reproduction rate. A female orangutan will not reach sexual maturity until she is about fourteen to sixteen years of age and will only bear an offspring once every eight to ten years.

The single greatest threat facing orangutans today is the rapidly expanding palm oil trade.

While there are millions of hectares of degraded land that could be used for plantations, many oil palm companies choose to instead use rainforest land to gain additional profits by logging the timber first. Palm oil companies also frequently use uncontrolled burning to clear the land, resulting in thousands of orangutans being burned to death. Those that survive have nowhere to live and nothing left to eat. Learn more about palm oil and its impact on orangutans here.

The species’ survival is severely endangered by logging, forest fires including those associated with the rapid spread of oil palm plantations, illegal hunting and trade. In the last few years, timber companies have increasingly entered the last strongholds of orangutans in Indonesia: the national parks. Official Indonesian data reveal that illegal logging has recently taken place in 37 of 41 surveyed national parks in Indonesia, some also seriously affected by mining and oil palm plantation development. Satellite imagery from 2006 documents beyond any doubt that protected areas important for orangutans are being deforested. The use of bribery or armed force by logging companies is commonly reported, and park rangers have insufficient numbers, arms, equipment and training to cope.

If current logging trends continue, most of Indonesia’s national parks are likely to be severely damaged within the next decade, because they are among the last areas to hold valuable timber in commercially viable amounts. The rapid rate of removal of food trees, killing of orangutans displaced by logging and plantation development, and fragmentation of remaining intact forest constitutes a conservation emergency. More than 1,000 orangutans are living in rescue centers in Borneo alone, with uncertain chances of ever returning to the wild.

Orangutans are unable to survive long-term in degraded and fragmented forests. Their fruit-dominated diet requires them to occupy large ranges to ensure sufficient supplies, and some individuals commute between feedings sources. Devastated forests offer few fruit resources and orangutans are forced out to roam in search of food. Large numbers were massacred while fleeing the flames and smoke during and after the extensive forest fires of 1997 and 1998. Similarly, orangutans do not cope well with selective logging. Selectively logged forest and old secondary growth contain only 30%-50% of the orangutan density found in primary forest.

To add pressure to the situation, orangutans have a comparatively slow reproduction rate. A female orangutan will not reach sexual maturity until she is about fourteen to sixteen years of age and will only bear an offspring once every eight to ten years.

The single greatest threat facing orangutans today is the rapidly expanding palm oil trade.

While there are millions of hectares of degraded land that could be used for plantations, many oil palm companies choose to instead use rainforest land to gain additional profits by logging the timber first. Palm oil companies also frequently use uncontrolled burning to clear the land, resulting in thousands of orangutans being burned to death. Those that survive have nowhere to live and nothing left to eat. Learn more about palm oil and its impact on orangutans here.

Additional Sources

- IUCN SSC Primate Specialist Group's Section on Great Apes A.P.E.S. Portal

- IUCN SSC Primate Specialists Group's Indonesian Orangutan National Action Plan 2007-2017

- UNEP's 2011 report Orangutans and the Economics of Sustainable Forest Management in Sumatra

- UNEP's 2007 report Last Stand of the Orangutan

- CBSG's 2004 Orangutan Population and Habitat Viability Analysis

- UNEP's Great Apes Survival Project 2002 report Great Apes: The Road Ahead

- UNEP's Orangutan Fact Sheet

Conservation Links

|

The Sumatran Orangutan Conservation Programme (SOCP) works to conserve viable wild populations of the critically endangered Sumatran orangutan. They do this by habitat protection, reintroduction of confiscated pets to the wild, education, survey work and scientific research. A great way to help support SOCP's valuable work is to adopt an orphan!

|

Orangutan Outreach’s mission is to protect orangutans in their native habitat while providing care for orphaned and displaced orangutans until they can be returned to their natural environment. They seek to raise and promote public awareness of orangutan conservation issues by collaborating with partner organizations around the world.

The Kinabatangan Orang-utan Conservation Program (KOCP) is a research and conservation programs in the heart of the Kinabatangan wetlands in eastern Sabah. The program has grown to include working on other wildlife issues including the endemic Borneo Pygmy Elephants. HUTAN-KOCP also works with local communities on human-wildlife conflict as well as alternative livelihood.

The Orangutan Conservancy (OC) is dedicated to the protection of orangutans in their natural habitat through research, capacity building, education and public awareness programs, and by supporting numerous on-the-ground efforts to save Southeast Asia’s only great ape.

The Gunung Palung Orangutan Project is a multi-faceted conservation and research program that works to protect endangered wild orangutans and studies orangutan reproduction, behavior, social organization and physiology within an ecological context. The Project's efforts are focused on the critically important population of orangutans living in and around Gunung Palung National Park in Indonesian Borneo.

The Sumatran Orangutan Society (SOS) work to raise awareness about the importance of protecting orangutans and their habitat; support grassroots projects that empower local people to become rainforest guardians; restore damaged orangutan habitat through tree planting programs; and campaign on issues threatening the survival of orangutans in the wild.

Yayasan Orangutan Sumatera Lestari – Orangutan Information Centre (YOSL-OIC) works with local people towards the preservation and regrowth of rainforest habitat and promotes orangutans as global conservation ambassadors for the rainforest ecosystem. OIC's focus is working on the front line to save Sumatran orangutans from life-threatening situations and sustain their survival by working with local communities living alongside orangutan habitat.

The Centre for Orangutan Protection (COP) is a direct action group of Indonesian people who campaign to bring an urgent end to the destruction of our rainforests and the killing of orangutans. COP strives to defend wild orangutans in Borneo forests from human brutality.

The Borneo Orangutan Survival Foundation's (BOSF) mission focuses on accelerating the release of Bornean orangutans from ex-situ to in-situ locations; encouraging the protection of Bornean orangutans and their habitat; increasing the empowerment of communities surrounding orangutan habitat; supporting research and education activities for the conservation of Bornean orangutans and their habitat; promoting the participation of and partnership with all stakeholders; and strengthening institutional capacity.

The Orangutan Foundation International (OFI) supports the conservation, protection, and understanding of orangutans and their rain forest habitat while caring for ex-captive orangutan orphans as they make their way back to the forest. OFI educates the public, school children, and governments about orangutans, tropical rain forests, and the issues surrounding orangutan and forest conservation and protection. OFI operates Camp Leakey in Tanjung Puting National Park, and the Orangutan Care Center and Quarantine (OCCQ) facility in Pasir Panjang.

The Orangutan Land Trust's (OLT) mission is to enable sustainable solutions that ensure safe areas of forest for the continued survival of the orangutan. OLT works to encourage policy makers to develop and implement strong policies and to uphold existing laws that contribute to orangutan conservation; support in-country initiatives and efforts to help deliver their aims; and develop appropriate and responsible partnerships to deliver tangible outcomes on the ground.

The Orangutan Tropical Peatland Project (OuTrop) is now a programme of Borneo Nature Foundation and works to protect some of the most important areas of tropical rainforest in Borneo, including the peat swamps of Sabangau, home to the world's largest orangutan population. OuTrop monitors the behavioral ecology of the forest's flagship ape and cat species, carries out biodiversity and forestry research, and works with local partners to develop conservation solutions and improve capacity for conservation in the region.

The Orang Utan Republik Foundation's (OURF) mission is to save the orangutans of Indonesia through conservation education, outreach initiatives and innovative collaborative programs that inspire and call people to action. OURF believes that saving orangutans means saving their forest home, the rainforests of Borneo and Sumatra, and that the protection of this habitat can only be ensured by the people of Indonesia and Malaysia.

The Orangutan Project (TOP) supports orangutan conservation, rainforest protection and reintroduction of orphans in order to save the species from extinction. TOP collaborates with several orangutan conservation projects, as well as providing habitat protection through its own Safeguard project - guard patrols that deter wildlife poaching, illegal logging and land clearing in Borneo and Sumatra. TOP provides technical and financial assistance directly to support conservation projects and orangutan rescue and rehabilitation centres.